Post 1: Iron and Riveted Steel Structures

This is the first in a series of blog posts on historical and antiquated structural and façade systems. When performing forensic investigations of structures, most structures and façade systems will consist of commonly used and conventional systems, such as light-framed wood construction, masonry, concrete framing and steel framing. However, in some instances, historical systems may be encountered. Such systems may be a holdover of a prominent historical construction system that was supplanted by a more modern construction method, or they may be the last remnant of a short-lived system that never received widespread adoption. Forensic experts with VERTEX are familiar with these systems and can assist with their assessment, repair, and retrofit.

This post focuses on iron and riveted steel structures as examples of such historical systems.

Iron and Steel Fundamentals

Iron has been in use since ancient times for various forms of construction, as well as for making tools, furniture and countless other useful items. The Ditherington Flax Mill building in England, completed in 1797, was the first iron-framed structure and is still standing today. Iron is both a metal and an element; in practice, common forms of iron such as wrought iron or cast iron contain some carbon and are not 100% pure iron. Steel is an alloy, consisting of iron and carbon; additional metals, such as nickel, are commonly added to steel to enhance certain properties.

Widespread adoption of a structural steel construction process did not commence until around 1880 following the invention and refinement of the Bessemer process. The Bessemer process was developed in 1855 and allowed for industrial scale production of relatively high-quality and consistent steel at greatly reduced cost. The development of these modern structural steel systems allowed for construction of longer span bridges and taller structures than had ever been created before.

Understand Material Strength before Repair or Renovation

Although superficially similar to modern structural steel systems, early iron and riveted steel structures have unique characteristics and limitations, which influenced their design and construction.

The strength of iron and structural steel is commonly taken as the materials’ yield strength, measured in pounds per square inch (psi). Wrought iron commonly has yield strengths of approximately 23,000psi while structural steel, such as A9 building steel when it first became available in 1909 had yield strengths of approximately 27,000psi. By 1933, this same A9 building steel had a yield strength of approximately 33,000psi. Later A36, introduced in 1960, raised this strength to 36,000psi. Today, modern structural steels with yield strengths of 50,000psi are common.

These improvements in metal strength represent advances in metallurgical understanding and refinement of production methods. The practical result is that modern steel has higher strength and more consistent material properties than either iron or historical riveted steel. This difference in material strength must be accounted for when performing forensic investigations of historical structures and is particularly relevant when undertaking repairs or renovations to such buildings.

Applications and the Implications of Materials on Performance

Historical iron and steel structures commonly utilized custom formed beams, columns and trusses. In some instances, the iron and steel members functioned as the building’s frame and served as a decorative or ornamental façade. This differs from modern structures which are typically constructed with an assortment of standardized steel shapes. In other cases, historical iron and steel frames were utilized to support historical facades of masonry or plaster. Figures 1 and 2 show the atrium of the Rookery building in Chicago, Illinois. The Rookery includes an iron framed roof structure, designed by Louis Sullivan in 1888. This iron framing was largely concealed behind marbled stone cladding installed during a renovation designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1905. However, elements of the original and unique iron frame remain visible.

Figure 1: The Rookery Building in Chicago, Illinois.

Figure 2: An iron column concealed behind decorative marble panels.

Figures 3 through 5 show the concealed structural frame behind the plaster clad interior framing and ceiling of a church constructed in 1904. The true complexity of this steel ceiling structure can only be appreciated when observed from the hidden catwalk framing above. The practical effect of these unique structures is that the specific dimensions and geometry of a structure must be carefully collected in order to model and analyze its performance. Original construction drawings can be an invaluable asset in this regard.

Figure 3: A historical church with plaster installed over a structural steel frame in Chicago, Illinois.

Figure 4: Steel frame visible behind the plaster facade.

Figure 5: Structural Steel Frame above the church ceiling in Figure 1

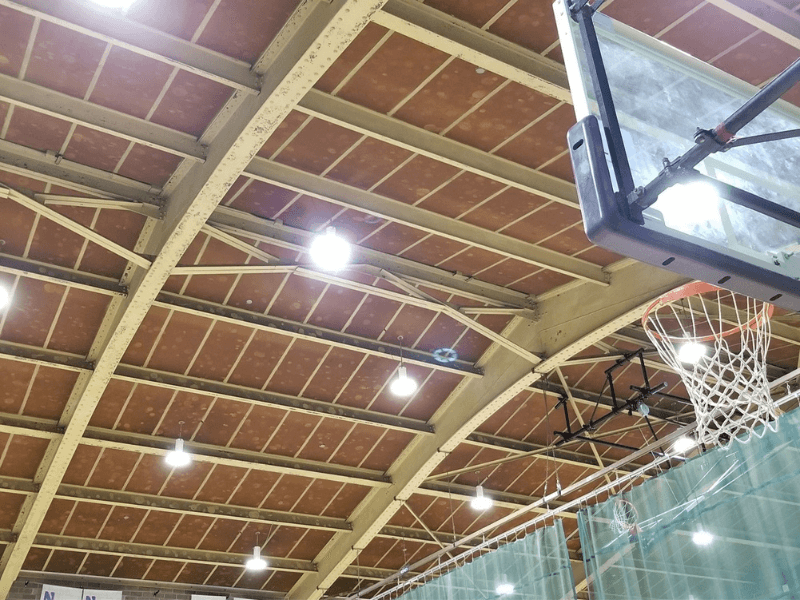

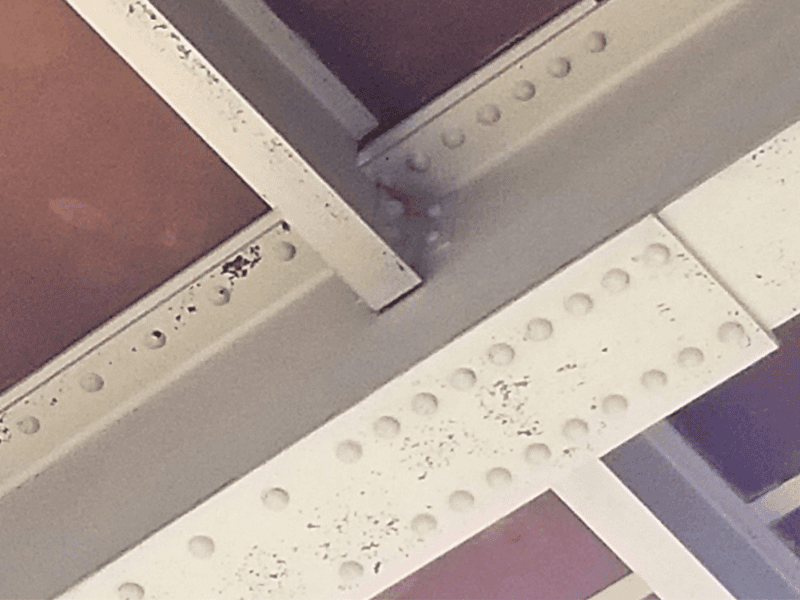

Instead of modern welded and bolted connections, historical metal structures commonly used rivetted connections. Rivets can be readily distinguished from bolts by their signature rounded head. This rounded head occurs during the installation process known as ‘peening’, when the rivet is pounded into a deformed shape to lock it in place. One disadvantage of rivets is that they cannot generally be removed without destruction of the rivet. Rivets also provide less strength than modern welding and bolting techniques. In the United States, rivets were largely supplanted by high-strength steel bolts starting in the 1960s. Figures 6 and 7 depict riveted steel connections on a gymnasium roof structure in Evanston, Illinois. Figure 8 shows a historical train station roof constructed with visible rivets.

Figure 6: Riveted steel gymnasium roof framing in Evanston, Illinois.

Figure 7: Riveted Steel Connection

Figure 8: Riveted train station roof.

Built to Last, But Only with Care

Due to their historical nature, corrosion and overloading are common causes of failure of these structures. A lack of maintenance and neglect and allow water to intrude through a historical structure’s roof or façade. This water can result in corrosion and deterioration. Indelicate renovations, such as installing multiple layers of roofing over older roofs, can result in overloading of a structure. This overloading can cause stressing and failure of the underlying structure.

The provided examples represent some of the unique structures and characteristics present in historical iron and riveted steel structures. Iron and historical steel structures, due to age, are susceptible to failures caused by deterioration from corrosion, neglect, or from a deficient design. Such failures require assessment by experts familiar with these systems. VERTEX has a team of experts familiar with the unique challenges of these structures, who can provide qualified assessments of these structures, and recommend action for repair and renovation. For more information, contact me Isaac Gaetz or submit an inquiry on our contact form.

In Part 2 of this series, we will discuss historical Terra Cotta facades.