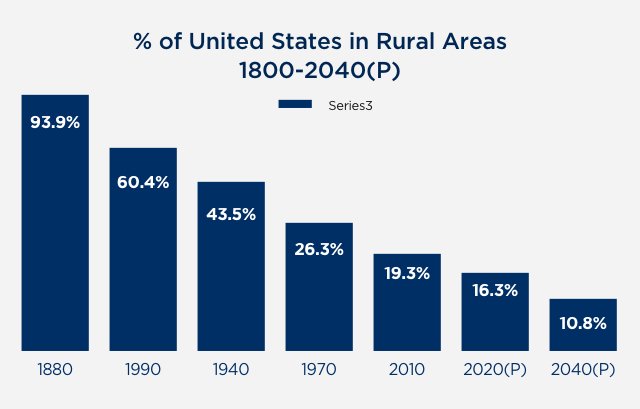

As a fairly new country (compared to, say, those in Europe and Asia), the United States started out with very few cities. In 1800, almost the entire population lived in rural areas. As industrialization took off, the economic shift produced the rise of cities.

Until the mid-1800s, virtually all those cities were on the East Coast. By 1970, only 25% of the population still lived in rural areas and now it is less than 20%. The Census Bureau is projecting the rural population to decline to 10% of the total U.S. population within 20 years.

Coinciding with the growth of U.S. urbanization is densification – that is, increased density of people living inside urban areas. Most of the East Coast has already densified, at least along the Boston-Washington corridor.

Here on the West Coast, other than in San Francisco, densification is only now beginning. For example, San Diego County has 4,300 square miles, but 85% of us live on just 689 of those square miles in 18 incorporated cities.

On an acreage basis, the overall density of the incorporated cities is 2.2 housing units per acre. We have a long way to go before we look like San Francisco, New York or Boston. We are one of the lowest-density major cities in the nation. San Diego County’s population continues to grow, and even more importantly, it has a diverse job base that will weather COVID-19’s effects better than most. Housing is our big weak spot. Last year, our county added 35,000 jobs, but unfortunately, we only permitted 8,000 housing units. As is often noted, our county is short about 100,000 units.

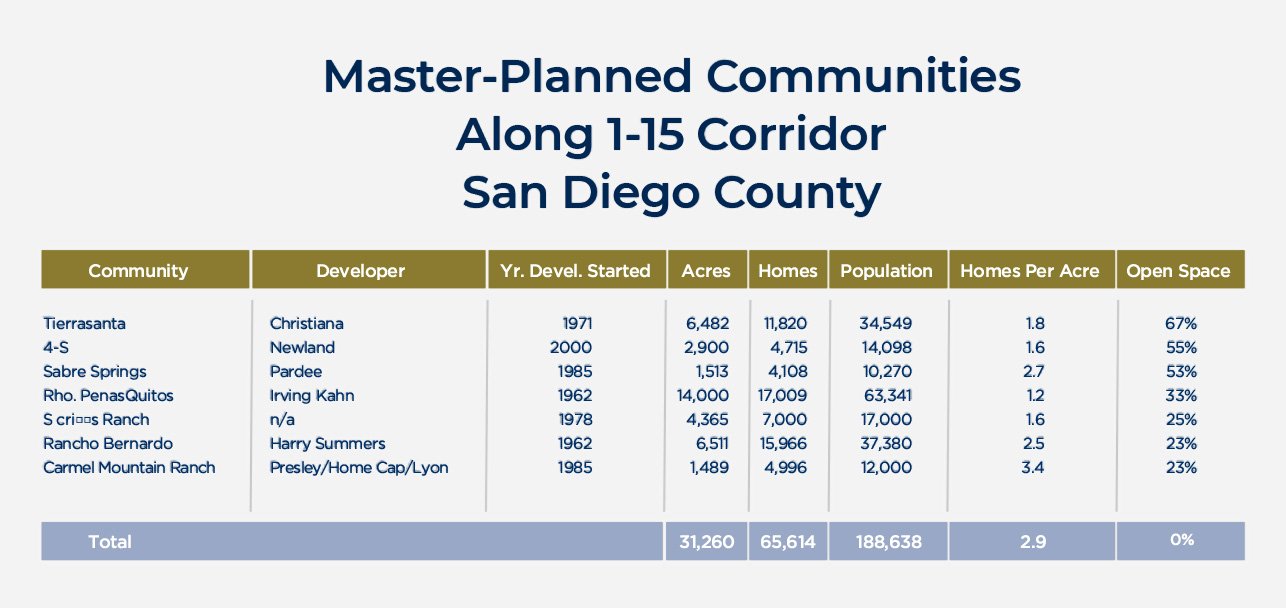

Density is not something that most San Diegans have a warm and fuzzy feeling about, and it is reflected in our communities. Almost all of them are primarily single-family and are low density. For example, in our great master-planned communities along the I-15 corridor like Rancho Bernardo, Rancho Penasquitos and Tierrasanta, the density averages less than 3.0 housing units per acre (see table).

You may notice the newest one among them was started 20 years ago, many of them are much older. Can you imagine trying to get approval for these existing seven master-planned communities along the I-15 corridor today? Those communities have 65,000 homes and house 200,000 persons. In fact, as we look around the county, we really only have two pure multi-family master-planned communities: Renaissance in University City (McKellar/HomeFed) and Millenia in Chula Vista’s Otay Ranch (Stratford). Each is composed of a combination of rental and for-sale housing. Both have been highly successful.

How San Diego accommodates densification?

At this point in time, densification is really mandatory for San Diego County to sustain our growing population. There are two kinds of densification to consider: vertical and horizontal.

Vertical construction is the most obvious way to increase density; however, it is a very expensive way to do so. That is because with any project higher than three stories, the materials change and construction methods become more complex.

Affordable housing developers find that vertical construction costs about $400,000 per unit in urban areas. Market-rate rental vertical construction in downtown San Diego typically costs more than $400,000 per unit. Other than very high-end apartment units by Bosa and other developers, little to no new vertical condominiums have been built in the county since 2008.

Yes, there will be some vertical construction near transit stops, but the reality is that those opportunities are few and, by themselves, will not solve the housing problem.

Horizontal construction may prove to be the most practical way to generate thousands of new housing units.

South of Interstate 8, there is enough land in Otay Ranch and around State Route 905 for the private sector to provide a substantial amount of attached and detached housing (sale and rental).

But, this comes with a caveat: North of I-8 is where most of the county’s jobs are.

The most obvious way to provide both sale and rental housing north of I-8 is to develop units on existing parcels. While there is land owned by the private sector, a substantial amount of real estate is owned by public agencies. Both the City and County of San Diego have hundreds of vacant sites or sites that are being used for miscellaneous storage and maintenance that could be utilized for housing.

If the City and County are serious about increasing housing development, including affordable (subsidized) housing, they have plenty of real estate they can repurpose and use for private-public partnerships.

Suburban cities like Escondido, La Mesa and Oceanside have substantial opportunities for redevelopment and actually need new housing development to support retailing and services in their urban cores.

Densifying Existing Neighborhoods

There are a few other horizontal densification opportunities that enterprising property owners can take advantage of.

The first is the Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU), or “granny flat.” This is a fairly painless way to add housing units, though not quite perfect for the family market. Granny flats can be free-standing or second-floor additions to one-story units. In either case, the land base is zero and in most jurisdictions, the fees are modest. We have more than 500,000 single-family homes in the County. With the recent state law changes, adding a granny flat has become a more viable opportunity.

A second way to add density in existing single-family neighborhoods is to slice the homes in half. Slicing horizontally can convert a two-story home into two one-story flats.

This is a particularly viable solution for retirees. In San Diego County, 20% of the single- family housing units are owned and occupied by folks over 65 (that’s 120,000 units). Since 1970, virtually all single-family housing development has been comprised of two-story units. Unlike the greater Los Angeles region, San Diego County has zero Del Webb or Four Seasons communities for seniors wanting to move to a single-story residence; if a senior wants to move down, there is hardly any inventory.

But, what if you slice a two-story home horizontally so the senior can live downstairs (no steps) and upstairs becomes a rental unit to provide additional income? It’s an alternative that is probably less expensive than building a granny flat and does not take up most of the backyard. Plus, it is less likely to meet resistance from neighbors.

A final option is building or converting to co-living apartments, which is just now gaining popularity among developers. This is distinct from property owners or renters putting up rooms for rent, although the concept is similar. The co-living apartment project is specifically designed so that residents each rent a room in a large unit that typically consists of four bedrooms and a common area.

This is not a new concept. In the late 1970’s, ConAm developed two major projects in Las Vegas wherein all the units were furnished four-bedrooms. One project was near UNLV and was, in essence, a dorm (Quail Ridge). ConAm still owns and manages it. The other was for unrelated single seniors. What goes around, comes around.

In summary, San Diego County needs to have a multitude of housing options to satisfy our ongoing growing pains. Right now, almost 40% of Millennials in the county still live with their parents. Without new alternatives, we will continue to see an increase in people commuting from Riverside and Orange Counties, Tijuana and maybe even El Centro, and these are really not realistic long-term solutions to our housing shortage.

This article was originally published by Xpera Group which is now part of The Vertex Companies, LLC.